Today, my friend @jillsmo of Yeah. Good Times. wrote a brave and thoughtful blog post that resonated with me. I started to leave a comment on it, but my comment got too long. (I know, right?) So, I left her a quick note and came over here to say the rest.

*DEEP BREATH*

I sometimes wish Helene were “normal.”

*EXHALE*

When I wish for “normal,” what I mean is that I wish Helene could have the same sense of humor, the same loving disposition, the same sweet smile, the same strong will that she now has right now — without speech delays, motor skills deficits, sensitivity to noise and stimuli, obliviousness to or irritation by her peers, tremendous anxiety attacks that consume her, a paradoxical need to hurt herself again (and again) after she feels pain, or the rollercoaster sleep schedule.

When I wish for “normal,” it is a short-hand way of saying I would gladly trade Helene’s doctor’s appointments, therapies, “social skills” classes, IEP teams, agency services, and rigid daily life for soccer games, dance classes, music lessons, the ability to travel and the freedom not only to have, but to enjoy, spontaneity and flexibility.

And, yes, I want these things as much for me and for our family as I do for Helene. Why wouldn’t or – more to the point – shouldn’t I?

But, wishing for “normal” does not mean I wish Helene wasn’t autistic. If someone handed me a pill tomorrow that would “cure” Helene’s autism, I would be simultaneously terrified to give it to her and to not. How do I not magically remove her challenges if it is within my power to do so? But, what if – what if – giving her fluent speech, gracious movement, regular sleep, a neurotypical response to pain, peer-aged social engagement or emotional stability, I simultaneously removed everything about Helene that makes up her personality – the very essence of what I love so much about her it hurts?

Why don’t I utter a desire for “normal” aloud? Why do I get upset when other people say to me, “Don’t you wish your daughter was ‘normal’?”

When I don’t say it, it’s out of fear and guilt.

I have two fears. First, I am afraid for myself. Second, I am afraid for the parents and children whose lives are touched by ASD. I am afraid that if I express this thought out loud, people in the ASD community, who have very strong opinions about what is “right” or “wrong” when living as or with a person on the spectrum, will attack me. I already feel so excluded and marginalized – on my own behalf and on my daughter’s – I don’t think I can take being rejected by the only community in which my daughter and I belong – objectively speaking, anyway. Second, I am afraid that if I express this thought out loud, I inadvertently send the wrong message to parents and children touched by ASD. My wish for “normal” is not a permanent state of mind for me. It’s not what I desire when I throw a penny in a fountain or blow out birthday candles or even when I read articles on developments in treatment of ASD. It is a recurring but fleeting thought that crosses my mind particularly when Helene is frustrated or hurt (physically or emotionally) by the challenges that life brings her. It is the manifestation of desire that I think most parents have in response to the difficulties confronting their children – I want to make it better / easier / safer.

Now, the guilt. My introduction to the autism spectrum community came with a barrage of messages about acceptance and advocacy: accept your child for who she is, and never stop pushing for her acceptance in and by broader society. These are good, important messages, because much of what I want for Helene will come from others understanding, accepting and integrating Helene into all aspects of society. I believe that these are my responsibilities as part of parenting a child on the spectrum. But, what I didn’t hear (or hear enough) about was how to address my own feelings about being a parent under these circumstances. Intuitively, I know that I am entitled to have feelings about this – both positive and negative. Being a parent is not a walk in the park under even the most idyllic of circumstances, because it inevitably involves the desire – or even the need – to control another human being. Still, the message I heard more often than not was that anything other than total and complete acceptance of my role and my child was failure – as a mom, as an advocate, as a human. So, when I find my mind wandering toward the forbidden wish that my daughter not face so many challenges and obstacles, I immediately feel shame. I feel as though I’ve betrayed her. And, I feel as though I betray the broader ASD community.

But, fear and guilt are not positive, healthy emotions. Walking around with that darkness does not make me a better parent for Helene – or Nate. It doesn’t make me a better member of this family. Quite the opposite, it makes me less effective, less convincing, and less able, because fear and guilt diminish the psychic energy necessary to be the advocate I do need to be; those feelings undermine my ability to create a positive space for Helene both within and outside the ASD community.

In fact, when I read Jill’s blog post, I burst into tears, because I felt relieved. I felt redeemed. I felt successful.

Why? Because, I happen to think Jill is a wonderful mother. I think she is an outstanding advocate not only people on the spectrum but for their parents and caregivers. And, because I respect her, hearing her say that she sometimes harbors the same feelings made the weight of all my bottled-up guilt and fear so much lighter. It made me believe that I am not alone. It made me believe that I’m not a bad parent. Do you know how empowering that is? Just think about that for a minute. Whether you are NT or on the spectrum, what motivates you more toward success: fear or positive reinforcement? If you are on the spectrum, did you find your relationship with your parent(s) more productive when they were anxious and filled with fear and worry or when they were able to just be with you?

So, what’s with my double standard? Why do I get upset when people ask me whether I wish Helene were ‘normal’? The most basic explanation is that I know what I mean by ‘normal’; I don’t know what you mean. That question is so very loaded by the vagueness of “normal” that I cannot possibly answer with a simple “yes” or “no.”

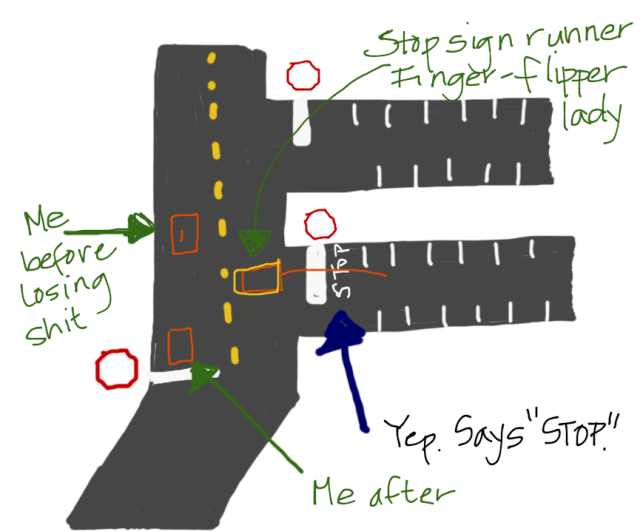

That makes me defensive, especially when talking to someone I don’t know. I feel like I have to explain and justify my daughter’s existence and my part in it. If you ask me this over a cup of coffee, when I’ve invited you to talk to me about raising children, I will feel comfortable enough to tell you the answer is “yes” (if you mean to ask me whether I wish life brought Helene more rewards than challenges); the answer is “no” if you mean to ask whether I wish Helene was not autistic or whether I am ashamed of, embarrassed by or angry at my daughter for being anything that she is. If you ask me this while she’s in the middle of a meltdown caused by too much sensory input or on her 55th rendition of “Itsy Bitsy Spider” to stave off the anxiety, I’m not going to take the time to make sense of ambiguities, I’m going immediately on the defensive, I will assume you mean “don’t you wish your life didn’t suck so bad,” and I will unleash my inner advocacy-mom-ninja. No, my life doesn’t suck, and neither does Helene’s, just because sometimes our lives are more frustrating than others’.

Remember me? Yeah.

Which brings me back around to fear and guilt. Do you know when people ask me the “normal” question the most often? It’s not over coffee. It’s not a question asked out of sympathy, empathy or even good will. It’s asked more like an accusation, making me simultaneously wish that you perceived my daughter as “normal” and feel shame that I have, in fact, wished for “normal.” It’s a horrible, confusing, depressing feeling, and instead of being able to reflect and answer that question in a way that would really advocate for Helene, I just lash out at the inquirer, which kind of proves his/her intended point.

So, I don’t say it. You don’t say it. It doesn’t get discussed. Until people like Jill are brave enough to put it out there — to risk the disappointment and anger of vocal members of the community, to risk being misunderstood – for the sake of reaching the parents out there who need to talk about it so that we do a better job of taking care of ourselves and parenting our beautiful kids.

Thank you, Jill, for making me brave enough to post this. Thank you to everyone brave enough to share in response.